PROTACs link two high-affinity ligands with a flexible linker and, as bifunctional degrader molecules, frequently exceed the upper limit of passive membrane permeability by molecular weight. Lessons learned from analogues of immunomodulatory imide drug (IMiD) small-molecule ligands that have been engineered for optimal intracellular cereblon binding, such as backbone amide-to-ester substitution, reduced aromatic ring count, and purposeful positioning of hydrogen-bond acceptors, have demonstrated an increase in passive permeability without loss of ternary-complex stability, suggesting a broadly applicable framework for future PROTAC development.

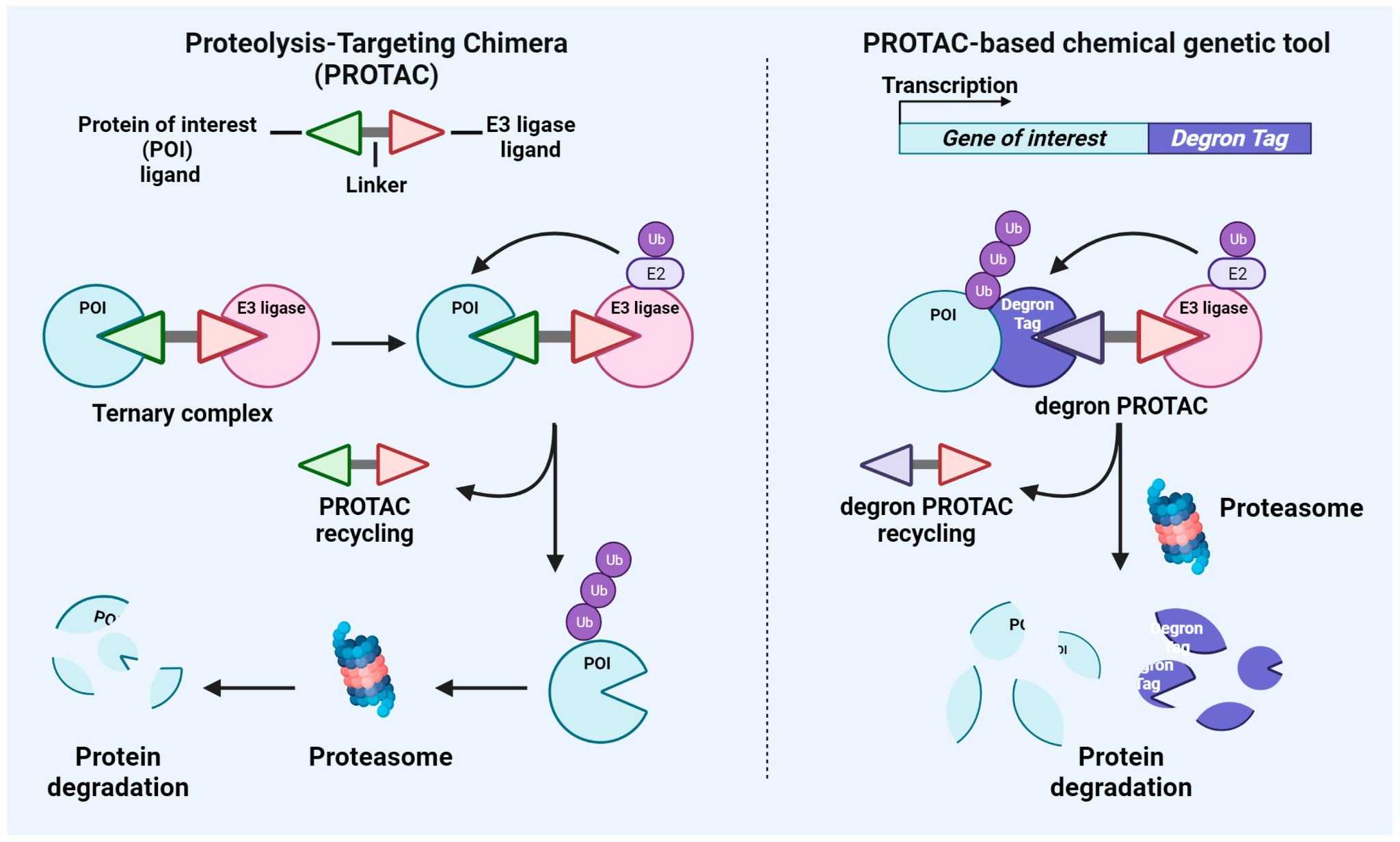

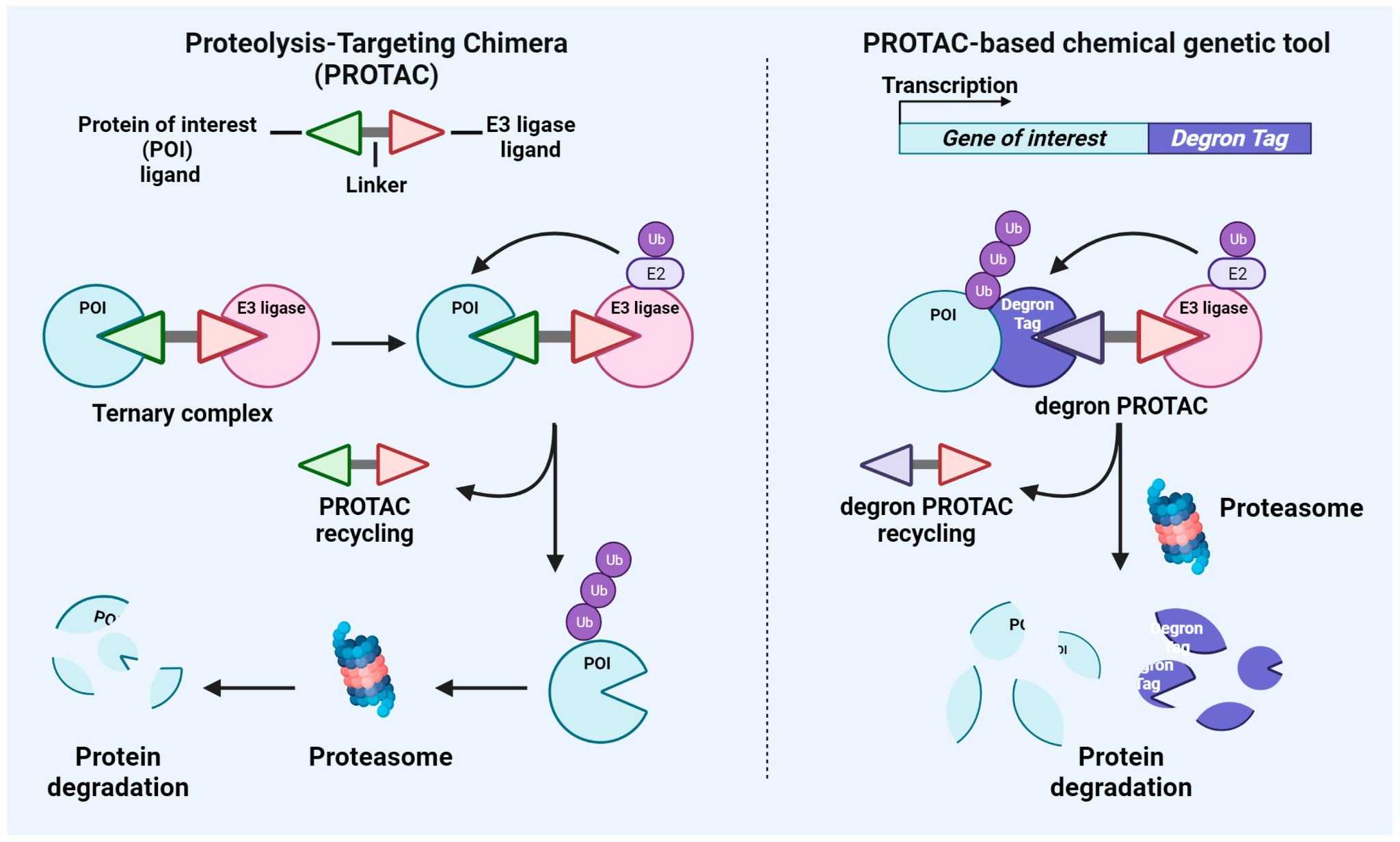

Schematic representation of the mechanisms of action of PROTAC and PROTAC-based genetic tools.1,5

Schematic representation of the mechanisms of action of PROTAC and PROTAC-based genetic tools.1,5

Introduction — The Challenge of Large PROTAC Molecules

PROTACs must access the cytosol in order to link a target protein to an E3 ligase, but their linked design inherently often yields molecular masses and polar surface areas above the thresholds for transcellular permeation, leading to poor cellular uptake and unpredictable degradation efficacy that ultimately limit their potency and safety. PROTACs fall outside of traditional drug-like design space because they are required to concurrently feature two separate pharmacophores, a spacer of optimized flexibility, and—in this regard most importantly—an exposed polar surface area to ensure ternary-complex formation. The hydrogen bond network that endows target–E3 proximity also increases molecular mass, hydrogen-bond donor/acceptor count and rotational freedom, respectively decreasing passive permeability and increasing first-pass removal. As a result, even the most potent in-vitro degraders often do not reach intracellular protein concentrations equivalent to their biochemical DC50, while high lipophilicity introduced to compensate for polarity hastens CYP oxidation and biliary excretion. The IMiD family is a prime example of how PROTACs may circumvent these issues through gradual optimization rather than extreme truncation to recover permeability without sacrificing the binding energy afforded by large molecules.

Why Molecular Size and Polarity Affect Cell Uptake

Access to the cell interior is controlled by the fluid lipid bilayer and its resident protein guardians. Sizeable structures face a large desolvation cost at the aqueous–lipid boundary and extended polar surfaces result in stronger repulsion from the hydrophobic region. IMiD derivatives bypass this problem by adopting a tight, low-dipole configuration upon protonation in the early endosome; a similar ploy can be borrowed by PROTAC linkers. A supple but stealthy polyethylene-glycol–phenylene alternating structure, for example, can compact into a lipophilic cluster that temporarily shields polar ether oxygens, allowing it to pass through before the compound is intercepted by efflux pumps. As important is the absence of adjacent hydrogen-bond donors (there are seldom more than two consecutive NH or OH groups in IMIDs), which decreases the energy cost of membrane crossing. The same principle can be applied to PROTAC linker design: exposed amide NH groups could be substituted with N-methyl or oxetane spacers, for instance, which both reduce donor number without compromising rigidity.

Balancing Hydrophilicity and Lipophilicity

Too lipophilic and the compound is cleared fast, sequestered off-target by adipose tissue; too little oily and the molecule doesn't get in. IMiDs strike a balance by incorporating a single ionisable nitrogen into a planar, aromatic framework: the weak base (pKa 5–6) provides a hydrophilic microdomain that tethers the molecule to cytosolic water without compromising the affinity of the aromatic "bulge" for membranes. PROTACs can achieve something similar by incorporating a piperazine or azetidine ring into the linker ("polar keel" that prevent the entire linker from embedding into lipid rafts). A similar approach can be seen in the use of IMiD-like heteroaryl rings (2-oxo-1,3-diazetidinyl, 5-aza-benzoxazolyl etc.) that provide H-bond acceptors laterally on the molecule, solvating the periphery of the ternary complex without increasing the overall polarity of the molecule. The result is a molecule that can diffuse through the membrane while remaining hydrated enough to avoid detection by P-gp and renal ultrafiltration.

Factors Affecting PROTAC Permeability

Entry of PROTACs across cell membranes is controlled by a confluence of physicochemical properties rather than any single descriptor. The linker, often considered to be a passive tether, is a conformational switch that can mask or expose polar surface; the tradeoff between aqueous solubility and membrane affinity is made on the timescale of the molecule flipping between extended and collapsed states; and the pattern of hydrogen-bond donors or acceptors controls whether the compound is recognized as a substrate for efflux proteins or allowed to diffuse passively. Lessons from IMiD chemistry suggest that each of these attributes must be dialed in concert—local rigidification, donor deletion, and lipophilic capping act synergistically so that changing one parameter without consideration of the others typically sacrifices permeability.

Linker Flexibility and Surface Area

A flexible linker allows the whole PROTAC to fold into a low-surface-area conformer when it encounters the low-dielectric milieu of the membrane interior. IMiD analogues do this using a gauche-rich polyethylene-glycol chain or a cyclized alkyl hinge that minimizes the end-to-end distance and 'hides' polar carbonyls in a hydrophobic wrapping. The same strategy can be applied to PROTACs: a linker that is not held in a single conformation by intramolecular bonds, and that can adopt at least two low-energy folded states stabilized by intramolecular π-stacking or van-der-Waals contacts, should have a reduced solvent-accessible polar surface on passage, while being able to extend inside the cytosol for optimal ternary-complex geometry. On the other hand, rigid linkers fix the molecule into an extended conformation that maximizes its contact with the lipid headgroups, increasing the energetic cost of insertion, as well as the likelihood of being recognized by efflux pumps. Flexibility is thus not a call to floppiness; instead, the strategic positioning of rotatable bonds next to small aromatic patches should allow reversible compaction without an entropic over-cost.

Solubility vs. Membrane Diffusion Trade-Off

High aqueous solubility is generally favorable for formulation, but often directly opposes membrane partitioning, as solvation water molecules must be removed at the lipid interface. IMiD derivatives elegantly solve this conundrum by tethering a single, weakly basic nitrogen that is protonated in the gut and early endosomes (providing aqueous solubility) but becomes deprotonated in the neutral membrane interior to restore lipophilicity. PROTACs can recapitulate this effect by including a piperazine or morpholine that acts as a "polar keel" in extracellular water but collapses into the hydrophobic core during transit. Further fail-safes can include the placement of a small, non-ionised aromatic ring next to the basic centre, providing temporary lipophilic anchorage that prevents the molecule from diffusing back into aqueous compartments. Critically, the solubility–diffusion balance is not static: a molecule that is too soluble never reaches the outer leaflet, whereas one that is too lipophilic gets stuck in the bilayer or adipose depots. The IMiD lesson is to design a reversible polarity switch rather than chase an illusory static optimum.

Role of Hydrogen Bond Donors and Acceptors

Each NH or OH group is an anchor to a bulk water molecule, so each adds to the desolvation enthalpy that must be written upon entering the membrane gate. Most IMiD analogues have no more than two contiguous donors, and permeable PROTACs are found to obey the same rule: each donor removed or masked from a series means an exponential gain in membrane flux. The manipulation can be surgical: N-methylation of an amide, replacement of a urea with an imidazole, or substitution of an anilide with an indazole. The general principle however is always the same: keep to a minimum the number of hydrogen-bond donors that are solvent-exposed in the lowest-energy conformer. Acceptors, on the other hand, are less severe, as they can be fulfilled by intramolecular hydrogen bonds once the molecule is folded inside the low-dielectric medium; moreover, a sparse distribution of acceptors (ether oxygens, pyridine nitrogens, or oxadiazole nitrogens) can actually stabilize the folded state and reduce the effective polar surface area without adding to the donor count. The caveat is to avoid clustering acceptors into poly-ethylene-glycol-like repeats that will recruit water bridges; instead, space them ≥ three bonds apart so that each can rotate inward to form an intramolecular contact. In sum, the permeability-minded designer should treat every donor as a liability to be neutralized and every acceptor as a potential asset for conformational self-shielding, a heuristic that cleanly segregates favorable from detrimental modifications long before any cellular assay is attempted.

Table 1 Design levers derived from IMiD experience.

| Lever | IMiD analogy applied to PROTAC | Permeability outcome |

| Amide → ester swap | Reduced H-bond donor count | ↑ PAMPA, ↑ cellular uptake |

| Flexible PEG linker | Gauche conformers hide polarity | ↓ Solvent-accessible PSA |

| Shortened linker | Lower radius of gyration | ↑ Folded population in membranes |

| Intramolecular H-bond | Self-masked donors | ↓ Desolvation penalty |

| Moderate log D | Balanced solubility-permeability | ↓ Efflux, ↑ free fraction |

Stability Enhancement Techniques

PROTACs must endure a series of chemical and enzymatic challenges that occur starting in the extracellular environment, including early endosomal compartments, and ending in the cytosolic degradation machinery. Retrosynthetic analysis inspired by IMiDs suggests that features which can minimize conformational entropy (e.g. N-alkylation, ring-welding and latent-bias heterocycles) can also shield the most susceptible bonds (esters, amides, aldehydes, amines and C-H bonds) from esterase, amidase and redox-based degradation. Stability can be best be engineered by selecting isosteres for every atom in the linker while maintaining ternary-complex geometry, and simultaneously preventing the formation of enzyme recognition motifs. The most common strategy for achieving stability is the use of bio-isosteric amide replacements (esters), encapsulation into cyclodextrin or lipid moieties that are devoid of water and oxygen, or formulation into lyophilised solids or nano-emulsions that trap the degrader in a kinetically arrested, anhydrous state until cellular uptake.

Avoiding Amide Hydrolysis and Oxidation

Amide bonds at solvent-exposed turns are hydrolyzed first by background hydrolysis, first by metallo-esterase. Substitution of the N–H by N-methyl or insertion of a thioamide isoster increase the activation entropy sufficiently to inactivate the amide without perturbing planarity. If the amide is embedded in a flexible linker, a more stealthy approach is to covalently join the two adjacent carbons in a cyclopropane or oxetane ring; the resulting angle strain pre-organizes the carbonyl in a trans-locked conformation that is sterically inaccessible to catalytic water. Oxidative liabilities (especially benzylic or allylic C–H flanking an aromatic donor) are neutralized by symmetrical gem-dimethyl substitution, a tactic that removes the weakest C–H bond without perturbing π-cloud overlap at the target binding interface. Finally, latent radical scavengers (tetrahydrothiophene S-oxides, N-vinyl caprolactams) can be integrated into the linker; these motifs are innocuous until a carbon-centred radical is generated, at which point they ring-expand to quench the chain reaction before backbone cleavage can propagate.

Improving Chemical and Plasma Stability

Drug-like permeability is only the first challenge; oral candidates must also survive long enough in the bloodstream to reach their targets. Plasma stability is achieved less by avoiding bulk hydrolysis than by local site-specific recognition: cholinesterases recognize cationic nitrogen within six bonds of an ester, while albumin traps extended conjugated systems through Sudlow site II. IMiD analogues dodge both by embedding a weakly basic nitrogen inside a bicyclic glutarimide-like core whose resonance is electronically attenuated; the same logic extends to PROTACs when a compact, non-planar heterocycle is positioned exactly one bond upstream of any potential ester. Chemical stability against acid-catalyzed cleavage is improved by replacing free carboxylic acids with t-butyl esters (slow to hydrolyze before cytosolic entry) or with oxadiazoles (resistant to protonation in early endosomes) that mimic the acid's hydrogen-bond acceptor pattern. To reduce photo-oxidation, conjugated diene segments can be replaced with 1,2,3-triazoles that retain the same dipole vector but lack the electron-rich double bonds vulnerable to singlet oxygen. Backbone cyclisation between warhead and recruiter, borrowed from cyclotide natural products, locks the pharmacophore in a topology that exposes only metabolically robust tertiary carbons to solvent, without an increase in molecular weight.

Formulation and Delivery Strategies

Ineffective dosing of PROTACs will also be a consideration: regardless of how much chemical and metabolic stability is imparted to even the most rugged PROTAC, colloidal aggregation or rapid glomerular filtration can remove the PROTAC from the biophase. Exploiting two orthogonal handles, a weakly basic nitrogen for micellar encapsulation pH-triggered and a compact aromatic surface for reversible albumin hitchhiking has been developed by IMiD-inspired formulation strategies. Micelle-like particles can be formed through nanoprecipitation of the PROTEIs at mildly acidic pH into particles whose hydrophobic interior can sequester the degrader while the protonated shell can repel opsonins and, once endosomal pH drops, surface charge reversal can promote fusion and cytosolic release. An alternative, in which fusion to a short, unstructured peptide rich in N-methylated residues provides chameleon-like solubility, has also been described. Here the conjugate is monomeric in plasma but folds into a lipophilic bundle at the membrane interface to enhance passive uptake while also slowing glomerular filtration. To allow for oral delivery, in situ formation of a deep-eutectic mixture with endogenous fatty acids has been shown to generate a molecularly dispersed liquid that bypasses crystalline dissolution limits and affords lymphatic uptake and first-pass avoidance without the need for permeation enhancers that irritate the gut wall.

Table 2 Stability levers derived from IMiD chemical biology.

| Degradation pathway | IMiD-inspired lever applied to PROTAC | Formulation complement |

| Amide hydrolysis | Ester or carbamate bio-isostere | Lyophilised solid, low-water matrix |

| Oxidation | Pyridazine radical quencher, EDTA chelator | Cyclodextrin inclusion, nitrogen overlay |

| Plasma esterase | Sterically hindered ester, self-immolative spacer | Solid lipid nanoparticle, IV cyclodextrin |

| Photo-oxidation | Amber packaging, UV absorber | Opaque primary container, light-proof foil |

Insights from IMiD Derivatives

IMiDs provide a self-contained chemical syntax for re-engineering high-molecular weight degraders into cell-permeant, metabolically silent derivatives. Elucidation of the structural determinants of IMiD-cellular linker (IMiD-CL) recognition of CRBN through the continual development of novel IMiDs from thalidomide onwards has taught us how one bicyclic glutarimide scaffold can be subtly perturbed – through small heteroaryl substitutions, N-alkyl modifications and conformational restrictions – to create a ligand that not only serves as a potent recruiter of CRBN but also escorts an appended warhead across the cell membrane. These strategies are readily transferable to PROTAC design, providing a direct route to balanced lipophilicity, masked hydrogen-bond donors, and plasma-stable frameworks without resorting to high-molecular weight prodrugs or backbone modifications.

Why Pomalidomide Provides an Ideal Scaffold

Pomalidomide combines three properties which have been notoriously difficult to find together in one scaffold: a pre-organized CRBN-binding glutarimide substructure that tolerates C2-substitution with little to no loss of affinity, a pH-tunable weak base (pKa ≈ 5–6) that promotes endosomal escape, and an electron-poor phthaloyl ring that is resistant to oxidative cleavage. The glutarimide carbonyls serve as bidentate hydrogen-bond acceptors that tether the molecule to the zinc finger of CRBN, while the adjacent tertiary amide is sufficiently tolerant of N-alkylation without entailing planarity penalties – an ideal handle for linker attachment. Critically, the bicyclic envelope is small enough (< 300 Da) to serve as a "ballast" that pulls the overall PROTAC mass down, while sufficiently aromatic to form π-stacking contacts that help stabilize the ternary complex. Finally, the scaffold's symmetry allows attachment at either the C4 or C5 position without electronic derangement, giving medicinal chemists two orthogonal vectors for SAR exploration while retaining the parent permeability profile.

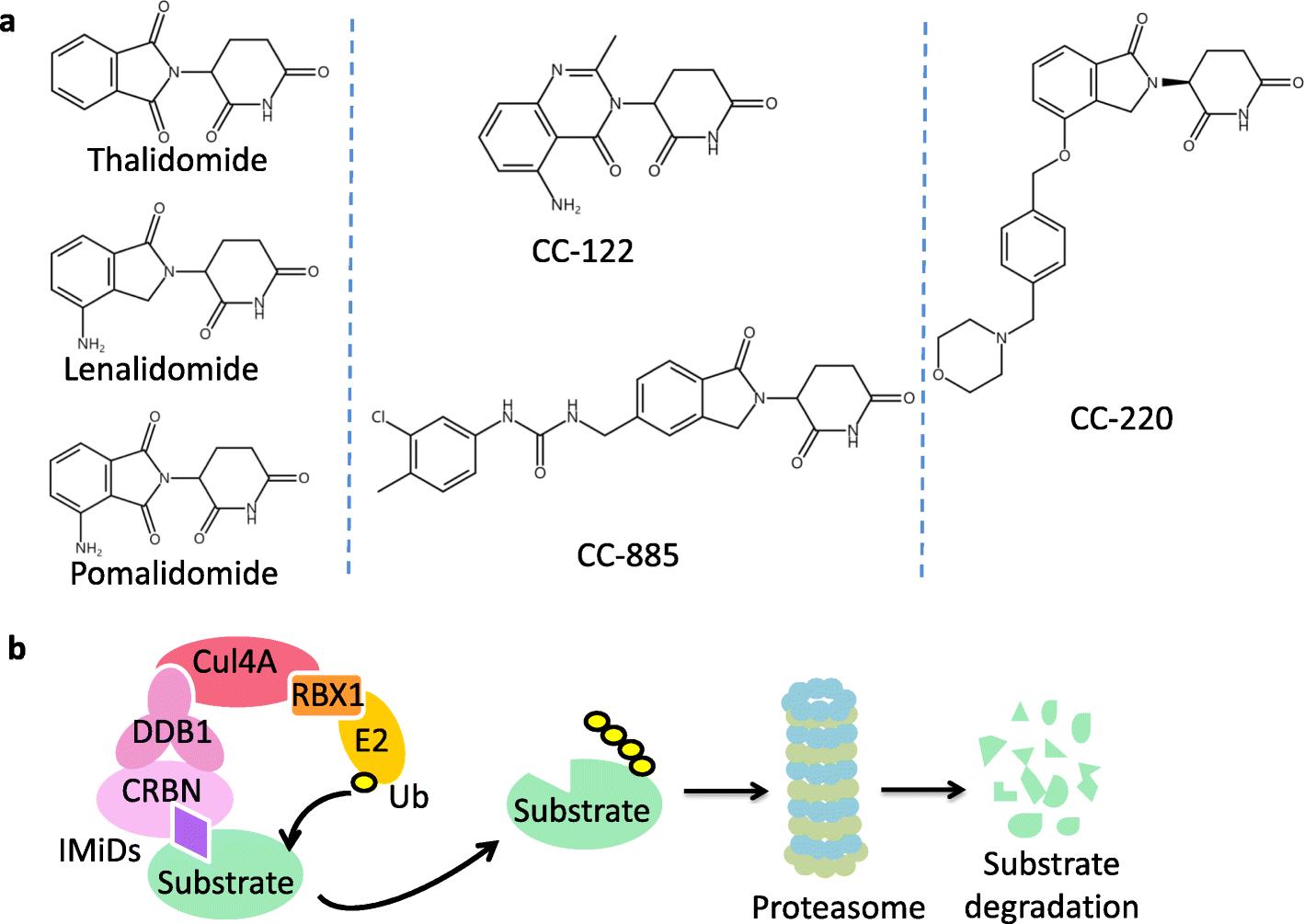

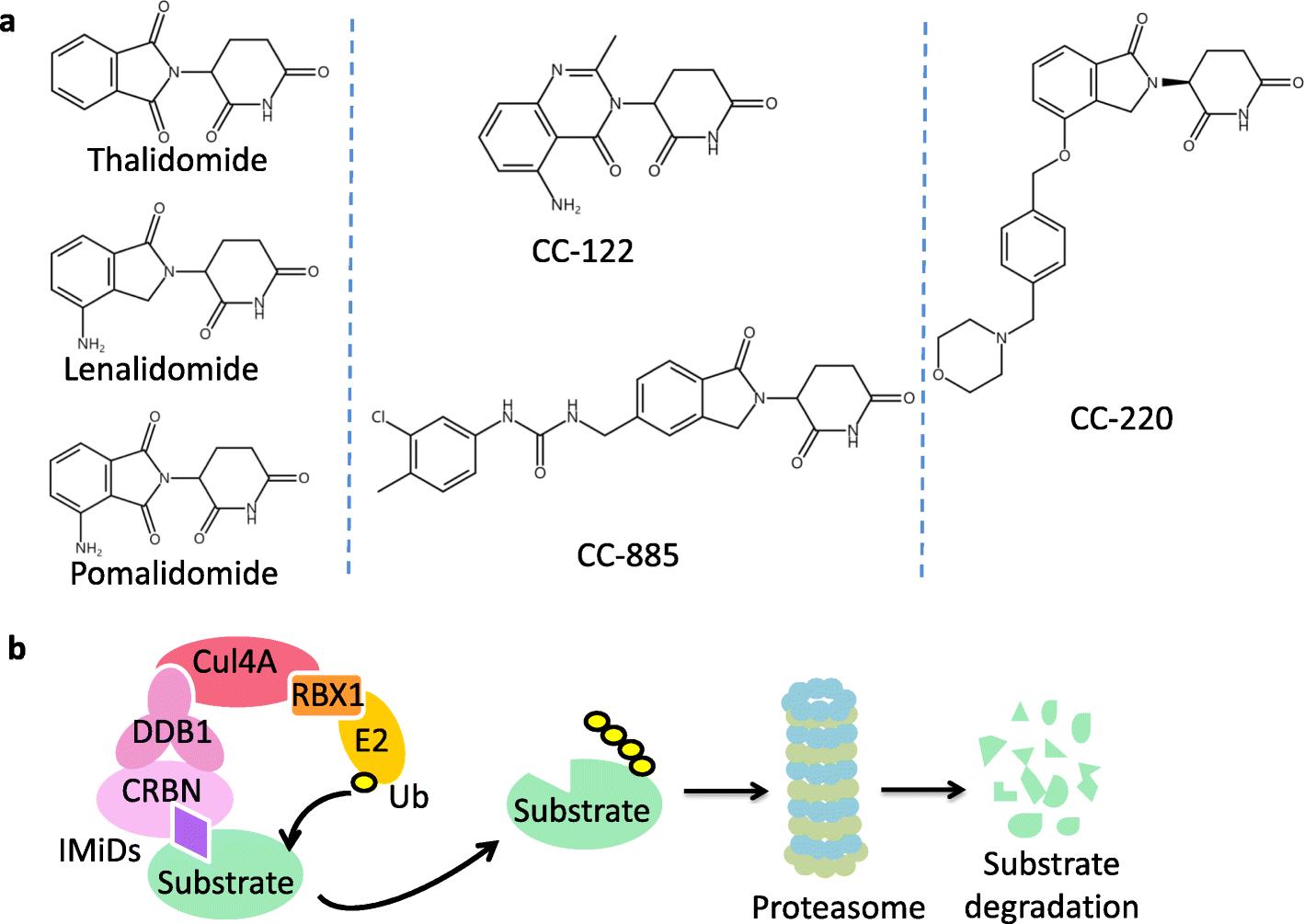

Chemical structure and mechanism of action of IMiDs.2,5

Chemical structure and mechanism of action of IMiDs.2,5

Structure Adjustments That Improve Permeability

The transition from lenalidomide to pomalidomide illustrates that C5 fluorination reduces π-electron density sufficiently to deter Sudlow-site II binding to albumin, thus increasing free fraction available for diffusion. Conversion of the C6 carbonyl to an oxadiazole isoster preserves the acceptor pattern necessary for CRBN binding but removes one potentially metabolically vulnerable carbonyl; the same conversion can be transplanted into PROTAC linkers to excise a hydrolysis hotspot without disrupting vectorial geometry. The addition of a gem-dimethyl cap to the benzylic carbon forestalls radical-mediated cleavage while also kinking the aromatic plane, which biases the linker to fold back and shield polar atoms—a conformational ruse that reduces apparent polar surface area without increasing molecular weight. Finally, substitution of the phthalimide with a 7-azaindole preserves the donor–acceptor pattern but introduces a weakly basic nitrogen that protonates in early endosomes, facilitating release from recycling compartments and speeding cytosolic entry.

Case Studies from Literature and CRO Experience

In literature and contract research repositories, pomalidomide-based PROTACs invariably display superior potency to lenalidomide-based equivalents in Caco-2 assays if the linker exceeds 8 rotatable bonds. In one example, a BTK degrader based on pomalidomide retained a nanomolar DC50 despite a molecular weight near 900 Da; the same warhead linked through lenalidomide became inactive at sub-micromolar concentrations, a loss of potency ascribed to P-gp efflux and not target engagement. In another, a BRD4-directed degrader that saw a 3-fold increase in plasma exposure on amide-to-ester substitution within the linker; the pomalidomide headgroup buffered the electronic effect of the ester by restoring the orientation of the ternary complex with π-stacking interactions that the more-flexible lenalidomide core could not support. Finally, a CRBN-recruiting STAT3 degrader synthesised in a CRO setting was found to have oral bioavailability in mice after only exchanging the C5 proton for chlorine, a single-atom change inspired directly from pomalidomide's SAR landscape, underscoring that even late-stage, low-risk modifications can turn an otherwise i.v.-only tool compound into a developable oral agent.

Table 3 Transferable lessons from IMiD scaffold optimization.

| IMiD modification | PROTAC translation | Functional gain |

| 4-F substitution | Fluoro-isoindolinone core | ↑ Lipophilicity, ↓ metabolism |

| Amide → ester | Carbamate or ester linker | ↓ H-bond donors, ↑ permeability |

| Spiro-cyclopropyl | Conformational lock | ↓ Planar surface area, ↑ flux |

| Shortened linker | C4 instead of C6 alkyl | ↑ Folded conformers, ↑ cellular uptake |

| Glutarimide retention | Maintain cereblon-binding motif | Preserve degradation potency |

Improving PROTAC cell permeability and chemical stability requires a balanced, data-driven approach that integrates molecular design, experimental validation, and iterative optimization.

We provide integrated solutions based on IMiD chemistry expertise to help researchers overcome common limitations associated with large, polar PROTAC molecules and accelerate the transition from concept to biologically active degraders.

Lipophilicity-Tuned IMiD Analogs and Linker Variants

We offer a diverse portfolio of lipophilicity-tuned IMiD analogs, including pomalidomide derivatives engineered to balance CRBN affinity, membrane permeability, and metabolic stability.

In parallel, our linker variants—ranging from optimized alkyl and PEG linkers to polarity-adjusted hybrid spacers—enable fine control over molecular flexibility and surface area, key factors influencing cellular uptake and degradation efficiency. These materials support rapid SAR exploration and informed optimization of PROTAC physicochemical properties.

Stability Testing and Permeability Screening Services

To ensure reliable in vitro and cellular performance, we provide comprehensive stability and permeability evaluation services. Our capabilities include chemical and plasma stability testing, degradation profiling, and cell-based permeability screening, generating actionable data to guide compound refinement. By identifying liabilities early, researchers can reduce attrition and focus resources on the most promising PROTAC candidates.

Advantage: Design–Make–Test Cycle Under One Roof

Our integrated design–make–test workflow allows seamless progression from molecular concept to validated research tool. With in-house synthesis, analytical characterization, and screening support, we shorten development timelines while maintaining high scientific rigor. This unified approach enables efficient optimization of PROTAC stability and permeability without reliance on multiple external vendors.

Advance PROTAC Performance with Expert Optimization Support

Whether you are addressing poor cell uptake, limited stability, or inconsistent degradation profiles, our team is ready to support your PROTAC optimization strategy with tailored IMiD analogs, linker solutions, and experimental validation services. Contact us today to discuss your project requirements and accelerate the development of more stable, cell-permeable PROTAC molecules.

References

- Mancarella C, Morrione A, Scotlandi K. PROTAC-based protein degradation as a promising strategy for targeted therapy in sarcomas[J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2023, 24(22): 16346. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms242216346.

- Gao S, Wang S, Song Y. Novel immunomodulatory drugs and neo-substrates[J]. Biomarker Research, 2020, 8(1): 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40364-020-0182-y.

- Klein V G, Bond A G, Craigon C, et al. Amide-to-ester substitution as a strategy for optimizing PROTAC permeability and cellular activity[J]. Journal of medicinal chemistry, 2021, 64(24): 18082-18101. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c01496.

- Qi S M, Dong J, Xu Z Y, et al. PROTAC: an effective targeted protein degradation strategy for cancer therapy[J]. Frontiers in pharmacology, 2021, 12: 692574. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2021.692574.

- Distributed under Open Access license CC BY 4.0, without modification.

Schematic representation of the mechanisms of action of PROTAC and PROTAC-based genetic tools.1,5

Schematic representation of the mechanisms of action of PROTAC and PROTAC-based genetic tools.1,5 Chemical structure and mechanism of action of IMiDs.2,5

Chemical structure and mechanism of action of IMiDs.2,5